International Trade & the Principle of Participation:

The American Experience from 1778 to 1945

By Rev. Frederick Edlefsen

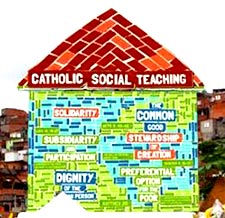

Participation in community life is not only one of the greatest aspirations of the citizen, called to exercise freely and responsibly his civic role with and for others, but is also one of the pillars of all democratic orders and one of the major guarantees of the permanence of the democratic system. Democratic government, in fact, is defined first of all by the assignment of powers and functions on the part of the people, exercised in their name, in their regard and on their behalf. It is therefore clearly evident that every democracy must be participative. This means that the different subjects of civil community at every level must be informed, listened to and involved in the exercise of the carried-out functions.” (Compendium of the Social Doctrine of the Church, 190)

The U.S. Constitution says that Congress has power “to regulate commerce with foreign nations” (Article 1, Section 8, Clause 3). Behind this clause lies the vision of a republic whose citizens participate in the politics of their destiny. This ideal is implied in the title “commonwealth,” which is held by four states: Virginia, Massachusetts, Pennsylvania and Kentucky. According to the Constitution, trade legislation is determined by elected representatives who are directly accountable to the citizens of a local “commonwealth.” When the Constitution became law in 1789, the idea of “free trade” with foreign nations was not popular. Alexander Hamilton recommended tariffs in his 1791 “Report to Manufacturers.” About a century later, between 1870-1900, the U.S. became an industrial player, paving the way to a greater role in the global theatre. This would create new tensions between “local democracy” and “foreign policy” and between the Legislative and Executive branches of government.

Before the Civil War, the U.S. was not reckoned a big player in world trade. The country was too busy going west. Moreover, Americans could move west if trade depressed wages. At that time, slave owning plantation owners were the only major “free trade” advocates because, for them, wages were zero. Meanwhile, England had the highest tariffs in the world until 1860, behind which it grew the world’s dominant manufacturers. “Free trade” became England’s ideology only after British manufacturing became strong.

Tariffs, free trade and the road to globalism

After the American Civil War, the U.S.’s booming rail and steel industries, mechanization technology and engineering colleges incubated behind a wall of tariffs, putting the U.S. on a path to globalism. By 1890, the U.S. surpassed Britain in manufacturing, and tariffs were the government’s main source of revenue. Trade politics would change after the Income Tax was ratified in 1913, as the federal government became less dependent on tariff revenues. After World War I, as the U.S. waxed and Britain waned in power, the U.S. was nonetheless a shy giant, reluctant to replace Britain as the world’s trade and finance leader. Taking on this role would require, among other things, a commitment to pursuing international “free trade.” In other words, the U.S. would have to reward its friends by purchasing their products, whereby those countries would earn the foreign exchange needed to buy the goods of America’s dominant industries. But the U.S. Congress, as mandated by the Constitution, was accountable to constituents who were in no mood for globalism, especially after the Great War. Americans wanted to take care of the home front.

Presidential power and local democracy

However, global capitalism collapsed in 1929, largely due to the U.S.’s unwillingness to provide financial, commercial and political leadership in the wake of a declining Britain. In response to the crisis, Congress listened to its ailing constituents and passed the Tariff Act of 1930, known as Smoot-Hawley, imposing tariffs on over 20,000 imported goods to protect America’s local economies. As the global depression worsened, the Secretary of State, Cordell Hull, popularized the idea that these tariffs aggravated the crisis. He was a globalist and a free trader. So in 1934, Congress did something unprecedented: it voted to give some if its constitutionally vested power to the president. It gave him the authority to reduce any U.S. tariff by 50% if other nations agreed to do the same, giving the president more leverage to negotiate foreign trade deals. However, this compromised the local communities’ voice, via their representatives, in the formation of economic policy. Nonetheless, after World War II, an economically booming U.S. maintained some of the world’s highest tariffs through the 1950s. But that would change.

After World War II, the U.S. was no longer a shy giant. The U.S. picked up where Britain left off, asserting its hegemony in the world of international trade and finance. This brought unprecedented stability to the “free world.” For the U.S., this also meant taking on “free trade” ideology, as global capitalism needed a dominant world power to provide a currency base, a system of exchange rates and oversight of international financial clearinghouses in order to keep cash flows stable and orderly. The U.S. asserted this role at the Bretton Woods agreement in 1945, which established all of these things, including the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD), which is now part of the World Bank group.

While the U.S. maintained some of the world’s highest tariffs throughout the 1950s, the “free trade” ideology would nonetheless be the ideal that would guide the Executive Branch’s foreign trade policy. It also meant that America’s local economies would have to give up a significant amount of influence over trade legislation. In effect, the American republic had to be partially re-constituted in order to be a global leader – something the Founding Fathers did not foresee.

Rev. Frederick Edlefsen is pastor of St. Agnes Church, Arlington.