PART THREE

International Trade and Democracy between 1947 and the Present

By Rev. Frederick Edlefsen

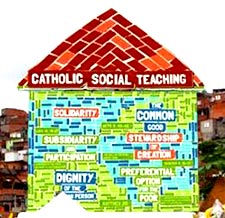

Challenges to Subsidiarity

Subsidiarity is among the most constant and characteristic directives of the Church’s social doctrine and has been present since the first great social encyclical. It is impossible to promote the dignity of the person without showing concern for the family, groups, associations, local territorial realities; in short, for that aggregate of economic, social, cultural, sports-oriented, recreational, professional and political expressions to which people spontaneously give life and which make it possible for them to achieve effective social growth. This is the realm of civil society, understood as the sum of the relationships between individuals and intermediate social groupings, which are the first relationships to arise and which come about thanks to “the creative subjectivity of the citizen.” This network of relationships strengthens the social fabric and constitutes the basis of a true community of persons, making possible the recognition of higher forms of social activity” (Compendium of the Social Doctrine of the Church, 185).

As the U.S. became the leader of the “free world” after World War II, American political power became increasingly “top heavy.” The Executive Branch more and more dominated national policy making. From the standpoint of Catholic Social Teaching, the “Principle of Participation” – as laid out in the Constitution – could only be maintained if the federal government chose to exercise the “Principle of Subsidiarity.” In other words, as the federal government got bigger, it would have had to limit its power over matters that affect the local populaces. Moreover, it would have had to allow local governments broad leeway in policy making; and the House of Representatives – the most participatory body of the federal government – would had have to keep its constitutionally mandated control over economic policy. But the federal government, for the most part, did not do this. Trade politics, among other things, would pose a direct challenge to “Subsidiarity,” and thereby “Participation,” largely with regard to the House of Representatives. “Free trade” ideology would often pit globalism against localism. Democracy and “free trade” ideology could not mix for long. Though this tension would ease during times of global prosperity, it would exacerbate during economic downturns.

Trade, Globalization and Participation

In 1947, the General Agreement of Tariffs and Trade (GATT) was formed by 27 nations, with the U.S. at the helm. It was a multilateral trade organization whose purpose was to pursue a “substantial reduction of tariffs and other trade barriers and the elimination of preferences on a reciprocal and mutually advantageous basis.” The GATT became the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 1994. When a nation signs on to this, it is committing its executive leaders to a negotiating process that practically requires overruling – or at least getting around – democratic and participatory institutions that give ordinary people influence over policy. Therefore, the Trade Expansion Act of 1962 established the Office of the Special Trade Representative (STR) as part of the Executive Office of the President. It was charged with recommending trade policies to him, as well as negotiating bilateral and multilateral trade agreements on his behalf. Today it has over 200 employees with offices in Geneva and Brussels and it own flag to boot. However, the STR is an oddity in the Executive Branch, as negotiating trade deals is part of Congress’, not the President’s, constitutional job description. But only a Chief Executive could deal with something like a GATT or WTO.

The STR was instrumental in the U.S.’s trade liberalizing leadership in the 1960s, with the help of the House Ways and Means Committee, which was chaired by the politically astute free trader from Arkansas, Congressman Wilbur Mills, from 1958-1974. Tariff and protection bills were usually blocked in the Committee, taking constituent pressure off of Congress. When Mills’ chairmanship of the Committee ended, the influence of congressional committees was in decline as well. Public pressure was turned up on Congress. Trade complaints from “special interests” (code for “local employers”) soared in the 1970s and early 1980s, especially by manufacturers of steel, steel and iron products, chemicals, textiles, footwear, hats and gloves, industrial and household appliances, automobile parts, machinery, wood products, canned foods, seafood and agricultural products in the wake of economic downturn. But as the economy recovered in the mid-1980s and 1990s, so-called “protectionist” (code for “looking out for the home front”) pressure on Congress was somewhat relieved, and the U.S. pursued the “free trade” ideology with full force once again. By the late 1980s, the U.S.’s attempt to assert “free trade” hegemony reached fever pitch when Secretary of Agriculture, Clayton Yeutter, and Minnesota Senator Rudy Boschwitz called for having farm legislation written in Geneva, not Washington. Congress had already ceded some of its power over tariffs in the 1930s. Now there were calls for it to cede its power over other forms of economic legislation. “Free trade” ideology and participatory democracy were again at odds. But the U.S. economy continued to expand on the wave of a technology boom throughout the 1990s. This made the passage of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) in 1994 politically doable, despite widespread skepticism. Local problems with NAFTA abounded, but they faded into the political background as the global economy boomed.

Centralization Leads to Economic Challenges

But by the mid-2000s, the world economy was losing steam, culminating in the 2008 market crash. Circa 2010, the US benefitted from sporadic oil fracking booms, but they would not last. Currently, Saudi Arabia and Russia are flooding the world market with oil. As working class incomes decline, the continuing loss of manufacturing jobs can no longer be dismissed. Popular pressure for local control has heated up. Political elites often write this off as “angry populism” or “anti-immigration” sentiment. But a more perceptive look at the problem reveals that America’s “blue collar” workers have a sense of losing local control and losing ground. Working class Europeans are expressing a similar frustration. This cannot be simply reduced to xenophobia, as working class citizens have a long history of being at odds with political elites who seem more preoccupied with multilateral agreements than domestic problems. Even among unions and immigration-friendly people on the “far left,” free trade is not in favor.

For many Americans, ideas like “free trade” may implicitly raise the question, “Free for whom?” Abstract ideas about “comparative advantage” do not resonate. Nor do references about being able to buy lots of cheap imports at Wal-Mart. It’s not just about what they can buy, it’s about what they can make. For ordinary people, a real “free market” would mean one that is free and prosperous both in consumption and in production. From the vantage point of a “blue collar” worker, a “free market” for financiers does not amount to a “free market” on Main Street.

Even for financiers and multinational corporations, international “free trade” has always been more ideology than reality. “Free trade” does not mean some “state of nature.” Nor does it mean a politics-free economy, as some theorists assume. Rather, a “free trade” regime must be underwritten by a heavily centralized government that maintains an effective monetary policy, sound institutions of currency and debt creation and strictly enforced trade, contract and limited liability laws. “Free trade” ideology speaks of abstracting “economics” from “politics,” but this is not what it does. Rather, it separates government from people. “Free trade” ideology is not really free trade, but it is the separation of democracy and state. The result: popular frustration with the establishment. For the time being, this means unconventional politics and unconventional candidates.

Rev. Frederick Edlefsen is pastor of St. Agnes Church, Arlington.